In this edition of “C-suite Conversations,” Judy interviews Doug Dean, Chief Human Resources Officer (CHRO) at Children’s of Alabama. With over 26 years at the organization, Doug brings a wealth of experience, humility, and forward-thinking wisdom to his role. From tackling burnout and embracing AI in HR, to fostering cross-generational understanding, he offers a candid perspective on what it really takes to lead with heart in today’s healthcare environment.

Children’s of Alabama is one of the nation’s largest pediatric medical centers, offering inpatient and outpatient care at its main Birmingham campus and locations across central Alabama, including Huntsville and Montgomery. As the state’s only health system dedicated exclusively to children, it also serves as the primary teaching hospital for UAB’s pediatric programs.

Q & A with Doug Dean

Judy Kirby: Doug, I’m so impressed that you’ve been with Children’s of Alabama for 26 years! What has kept you there all this time?

Doug Dean: In my case, Judy, I think it’s not much more complicated than finding my ideally suited leadership role. Now, if I were not mentored well early in my career, or if I had not learned to be adaptable, then I might have found that 26-year tenure shortened by choice or by chance. On average, almost all of us in leadership at any organization have had to reinvent ourselves about every five to seven years – maybe not wholesale, but in meaningful ways to stay aligned with our organization’s strategic priorities. But thank you for the compliment. It mostly means I’m not 30 years-old anymore!

Judy: You’ve seen the evolution of the role over 26 years that we now call the Chief Human Resource Officer. What do you predict will be the focus of the CHRO role for the next three to five years?

Doug: I love that question. It is almost universal that if you ask not only CHROs like myself, but CEOs and COOs what keeps them up at night, they almost all now point to concerns about staffing the organization, developing leaders, and the challenging supply of talent. So, talent acquisition, recruiting, and retention are in the CEO vernacular these days, which means that the primary impact by CHROs and their teams is at the top of the leadership agenda.

Judy: A lot of the CHROs feel that they don’t have a seat at the executive roundtable. Why is that?

Doug: I don’t think there’s, as perhaps some colleagues may believe, an inherent disdain for HR leaders or underestimating the importance of the human resources function in an organization. If you’re not at the executive roundtable, it is often a self-inflicted wound if we’re honest. Frankly, some don’t polish their skills and learn to be a compelling presenter and use data to make their case compellingly. So I think we still earn our seat on the big issues.

I try to hire people who are smarter than me and then turn them loose to research who’s ahead in the world, especially in the healthcare industry. Are there good ideas we can borrow or adapt? In HR the trend can be to seep into being transactional and focus on pushing mundane work out the door. You really need to wall off – quite literally, physically – the strategic planning work and protect it from the transactional grind.

Judy: How do you see AI influencing HR in the future?

Doug: I was at a seminar recently given by a well-known international HR consulting firm, and they presented some findings from a survey of a large group of HR leaders. Not surprisingly, only about 25 percent of those surveyed are doing what they consider meaningful AI implementations. We too are playing a little bit of catch-up, but I’ve started. I do think we need to step on the accelerator with AI in the HR profession. The cost of waiting or being risk averse as a “late adopter” might be higher and more painful.

It’s a simple step, but I encourage my HR team to play with simple AI applications, get their feet wet and go to conferences where people are talking about what’s already happening in HR with AI.

For example, almost all of us in HR love to use video as a communications method. It’s just more compelling in many instances. There is AI technology that produces very high-quality videos for your messaging with incredible speed and for dirt cheap.

I think we’ll also see more use of AI in the screening of candidates, and candidates more comfortable interacting with a bot. It’s already happening. Then, the only candidates that come across my and your desks will be the finalists, which reduces costs and the time required.

Judy: Everyone in healthcare hears about physician and clinician burnout. I saw an article at the end of 2024 about HR leader burnout too. What are your thoughts?

Doug: I think that there’s a constellation of issues, and many of them don’t have anything to do with what we experience at work. For some, maybe it is just life as they envisioned it in terms of the architecture of life, whether that’s relationships, friendships, or even the stress and joy of raising children. There are unprecedented pressures and demands on people outside of work, and yet we bring our entire self to the office. I think companies are only recently coming to terms with that – that we don’t want you to compartmentalize.

But I think that there are ways to forestall and overcome burnout by deliberately taking on new challenges at work that excite you. That might mean redirecting your career and it might mean a temporary drop in salary. What’s the saying? “If you do something you love, then you’ll never work a day in your life.” It’s kind of sappy, but I do think there’s a kernel of truth to it. So, I encourage my colleagues who have very long tenure like myself, to start to be a little selfish in their non-work life. “What things really give you joy when you’re away from work?” If you can optimize those and make sure you practice great self-care, that you’re eating well, you’re exercising, you have good experiences outside of work, I think it can dramatically forestall the ill effects of burnout through a more holistic approach to life.

Judy: There are multiple generations in the workforce. From your point of view, what are the differences between those generations in terms of what they want from the work experience?

Doug: What we’re experiencing is the outflow of baby boomers who have run our organization for a long time. They’re so loyal and hardworking. And there is an inflow of millennial and Gen Z workers. Our total population at Children’s of Alabama is just under 6,000, of which about 65 percent are in the millennial and Gen Z category. To me they seem so young, but you know what? They’re incredibly well-educated, well-trained, very high-tech, and very compassionate about what we do and what they bring to the table.

You’ve got to pay attention to the demographics. The minute our leadership starts building the work experience around people in my demographic – I’m between boomer and Gen X – we are making a strategic error because the reality is we’re only going to continue replacing experienced workers with younger people. So, we need to get really good at understanding these workforce demographics, their work preferences, and how they like to be led, the kind of feedback they want. It’s become a very big deal.

Judy: What differences are you seeing among the younger demographics?

Doug: Sometimes when we’re talking about generations, it still feels like we’re stereotyping with a broad brush. Dominant profiles of demographics like Gen Z, millennials, etc. are useful in many ways, but we should always be open to the possibility that an individual’s life experience and their upbringing and who they are might put them outside the mold. You might meet a Gen Z in their late 20s who is an old soul, and talking to them might sound like you and I having a conversation, Judy.

The differences I see mostly with the younger generations are that they really value when you check in with them so they can ask, “How am I doing?” Sometimes they literally mean, “Am I secure in my job? Am I performing well?” So, leaders and future leaders need to develop the habits of sincere and authentic ways of talking about development, growth, and performance, and paint a picture for the younger generations. “Hey, you’re really on track to be in position for advancement soon.” Frankly, they’re more like free agents, which I do not equate with disloyalty. I think younger workers have seen that if you stay at a company for 20 years, you can still get RIF’d or laid off. So, what’s the point in excessive loyalty, they may think? And I don’t feel that is a cynical point of view – maybe they’re the smart ones.

Judy: Relocation continues to be an issue for a lot of executives or high-level leaders. What have you implemented to get the talent you want to move to Birmingham, Alabama?

Doug: You need to have the good fortune of city planners and leaders who are working on the quality of life. For example, my HR colleagues and I had nothing to do with the food and wine scene here in Birmingham, which has become unbelievable! When my friends from cities like Atlanta, Chicago, New York, and Boston come here, they rave about our fine restaurants. If it’s a family moving here, there is access to very high-quality schools. The natural resources include freshwater lakes, and in 3 ½ hours you can drive to the world’s most beautiful beaches in Destin, Florida and Gulf Shores, Alabama.

Some may come here kicking and screaming because of outdated preconceived notions, but once they’re here and they get plugged into what we mean by southern hospitality and the friendliness of a place like Birmingham, Alabama, they want to stay. We see it time and again.

Judy: What testing, interviewing techniques, or other strategies do you employ to make sure you hire the right person in every position?

Doug: This is going to sound like a paid endorsement but we’re about 10 years into the very successful use of an instrument called Judgment Index. It’s not a personality or IQ test, neither of which is very predictive of performance, especially in a leadership role. But we believe strongly in the Judgment Index, which is considered to be among the most reliably validated and tested assessments of its kind. It is much more predictive of performance in a work setting, especially in a leadership role.

Judy: Over the course of your career as the HR leader, how have you partnered with departments to improve their culture?

Doug: What’s interesting about your question is that you’re invoking the notion of not just the organizational culture, but a culture within a particular department. I think we’ve done that but I would describe it as informal. I’d be a little nervous about a department veering away from the organizational values much at all. If they are able to take our organizational culture and values and put their own unique stamp on it, as long as those two are compatible, that can be a beautiful thing. It’s mostly my OD leaders having a lot of conversations with a director and asking, “What does your team need? What will attract talent?” For some, that might mean offering four 10-hour days and letting people have long weekends during the summer. For others, it might mean the ability to cross-train so people feel like they’re growing and developing. So, it can be a wide array of things.

Judy: What is your organization doing when it comes to remote and hybrid work, and what has been successful for you?

Doug: At the start of the pandemic, we had to send upwards of 1,800 staff members home. It was for safety reasons; we had no choice. What’s that phrase, “Necessity is the mother of invention?” If we didn’t do something, their income would be impacted. So, we quickly got very good at people working productively from home. Of course, patient care is not remote, but the corporate service areas.

Culturally, we think great things happen with teams when they’re physically in contact and come to a central office. That’s not to say this subject hasn’t been controversial. People got used to being at home and working remotely, and it was popular. But except for IT workers and a handful of other areas, we’re mostly back at the office, and that’s unpopular with some. Maybe they have work-life balance challenges. But I think there is a socialization and a mental health that can come with going in and being with people and not getting too isolated in your own home space for long hours. I do expect that the world will compel us to offer some hybrid work-from-home options, but we’re unlikely to have leaders leading their teams remotely.

Judy: Is IT still fully remote?

Doug: It is case specific. For those in IT doing a lot of heads down systems work, it doesn’t require a great deal of face-to-face communication, many of those are fully remote. Others want to come in a few days a week, so they are taking creative approaches that are driven by the nature of the work as opposed to enacting broad, deep rules. We’re trying to be nimble and flexible, and when we can, we adapt the rules to what will make the most sense for a particular employee.

Judy: There has been a lot of quiet quitting and early retirements in healthcare. What are you seeing as CHRO at Children’s of Alabama, and how are you addressing these challenges?

Doug: For more than 15 years, we were successful at keeping voluntary turnover under 12 percent system-wide, which is remarkable. Then in the wake of the pandemic, we joined the throngs of hospitals where it spiked to over 20%. The worst year was probably 2021. That was a shock to the system that forced us to ask a lot of difficult questions around what our workforce planning assumptions should be.

One strategy when good people leave the system is that maybe they’ll be interested to come back and work with us again in the future. So let’s get really good at re-recruiting them because we’ve already made this enormous investment in them. And, when we make an offer and fill a single position, we should still be very interested in the two or three runner-ups. They were talented enough to be a finalist so could they be a quality hire for another position?

Judy: Were you successfully mentored at key points in your career?

Doug: I was very fortunate along the way that in several cases, my bosses were friendly and didn’t always have to act like my superior issuing directives, and we became mutually respectful. My experience has been that people are usually delighted to share their lessons learned, and what they see in you, where you can grow and improve your chances to have impact as a leader.

My advice is to be a sponge when you’re around leaders you really admire and become a student of their leadership. If your company will help fund it, I highly recommend a quality executive coach as a safe space where you can go talk about a weakness or a specific mismanaged situation, and get coaching on that. Maybe they’ll do a 360 with your peers and subordinates, but be prepared for that to sting a little and point out some areas that you really need to improve. I think it’s just being humble and never feeling like you’re a finished product, and finding the joy in continuous development.

Judy: I hear from HR executives that often, one of their strongest relationships is with the CIO because IT touches everything. From your experience, what does a really strong partnership with the CIO look like?

Doug: I admit that we don’t speak the language of IT, but the CIOs I’ve worked with understand and are happy to translate. I think it’s critically important that you hire a very capable, strong HRIS leader so that you have a translator walking along with you. We’re trying to turn data into useful management information to operate our workforce and do all the powerful things that you can with technology. So, build a relationship and get to the point where your gap in technical knowledge compared to a CIO’s does not become an impediment.

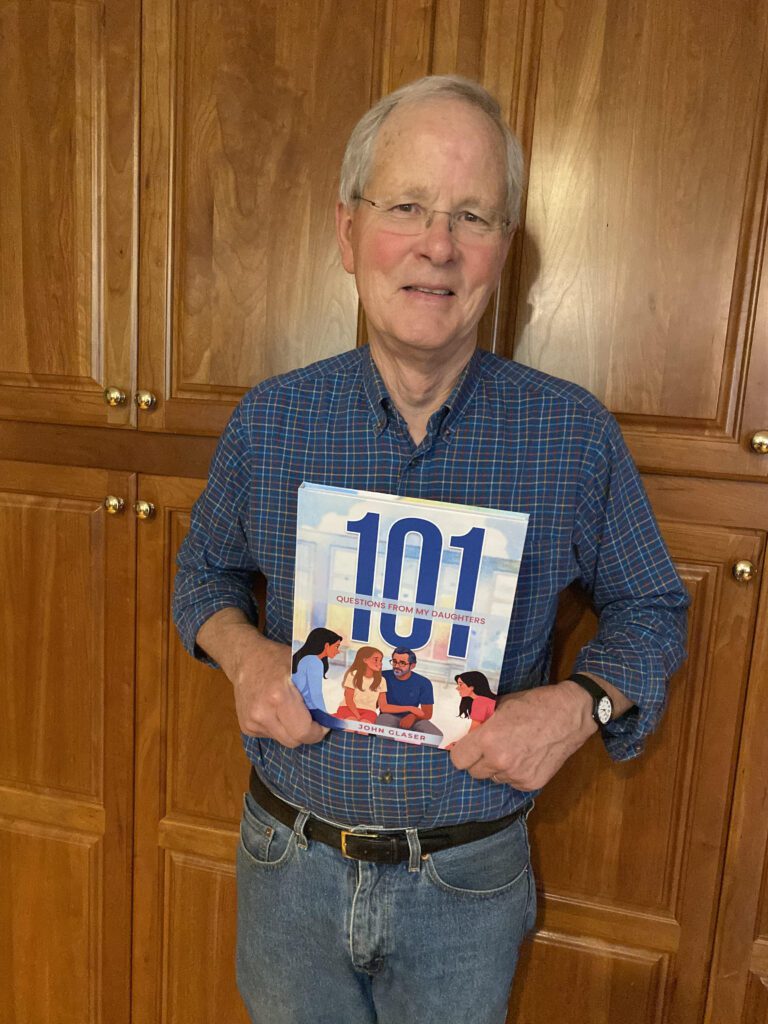

Judy: What do you like to do in your free time?

Doug: I love to write. I was an English major and when I do eventually retire, I look forward to writing fiction, or I should say “completing” because I’ve got a couple books underway. My motivation is not to attract a big publisher, or money. If that happens, then great, but it’s just for the love of writing. I want to go through that experience to keep the mind and heart engaged.

And anything outdoors, whether it’s on the water, in the woods, on a golf course, or just sitting on my back deck with my sweet little yellow lab. I love the fresh air, and I think getting into the great outdoors is good mental health advice for all of us.